Prodigal Shepherd: Fr. Pfau, First Priest in Alcoholics Anonymous

"Fr John Doe finds Alcoholics Anonymous"

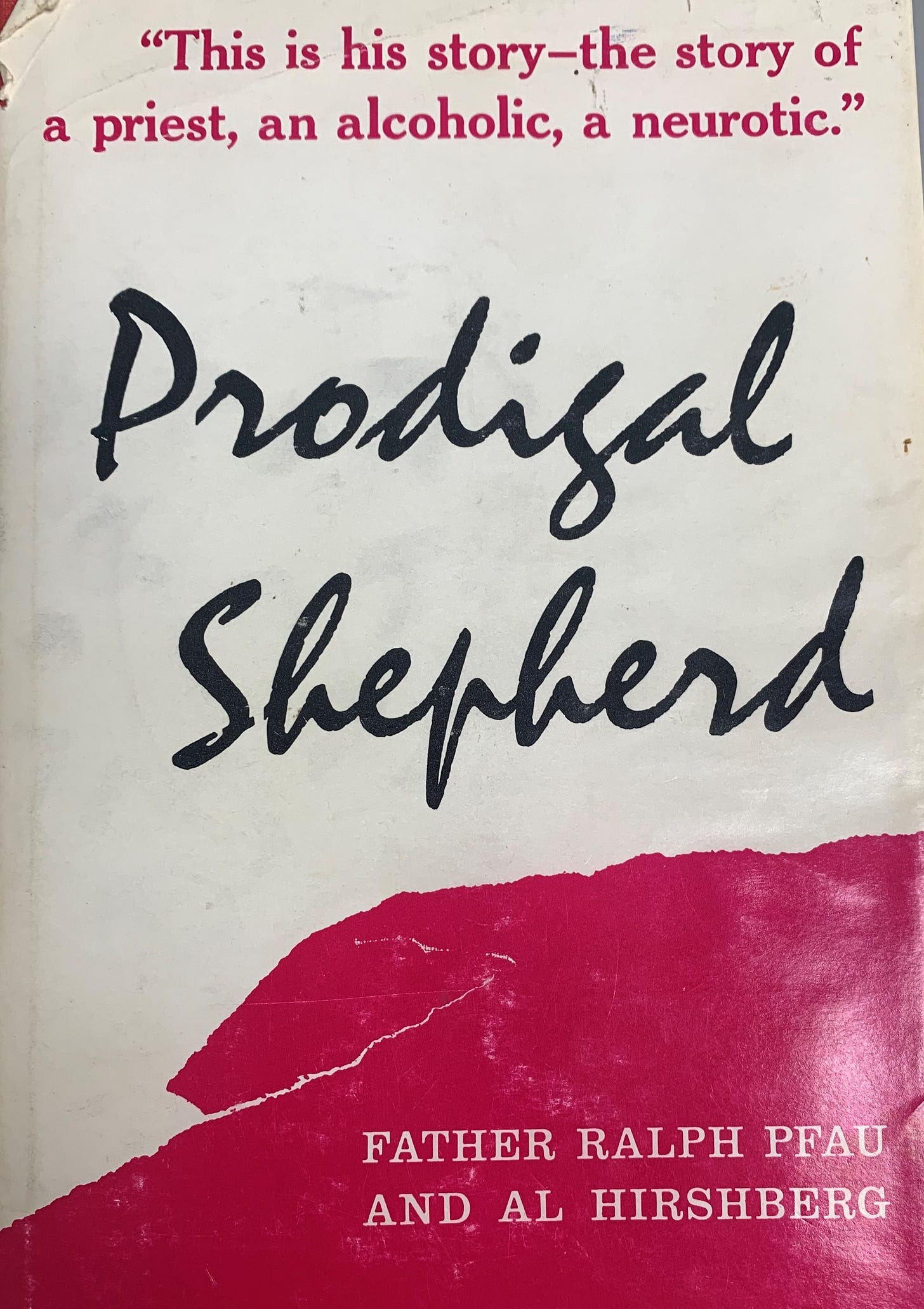

Being a lover of history, a few years ago I picked up a volume titled Prodigal Shepherd. It is an autobiographical account of Fr. Ralph Pfau, the first priest in Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.) who got sober in A.A. Group # 1 in Indianapolis, Indiana. His sponsor was the late Doherty Sheerin, the founder of A.A. in Indiana, who died in 1953 with fifteen years sober.

Ralph was born the youngest of seven boys, no sisters in the brood. His dad, who was of French extraction, died when he was four. His mother, of German descent, once patted him on the head as a five-year-old saying, “This is Ralph. He is going to be a priest.” And so it was, he departed for St. Meinrad Seminary in Indiana. After getting ordained a priest, he made vow not to drink any alcohol for one year; this he did partly as penance, and partly because he knew that alcoholism was hereditary in the family.

Within five months of his ordination to the priesthood in May of 1929, his mother became deathly ill from cancer. On October 13th, the Feast of the Holy Rosary, the doctor announced that she did not have long to live in this world. Fr. Pfau, together with his brother/priest, Fr. Jerry, received permission from Bishop Chartrand to offer Mass at their mother’s home in Vincennes, Indiana; after Fr. Pfau gave her Holy Communion, she died, and then Fr. Jerry said the second Mass immediately following, saying to his brother, “It will be the first Requiem Mass for mom.” She died in the early hours of October 14th, in between the two Masses offered by her sons.

After the death of his mother Fr. Pfau departed for Fordham, a Jesuit University in New York City. It was in the Big Apple that Fr. Pfau happened to meet a friend of his from back home in Indiana, David Batterly, a lawyer. The days of Prohibition were still in full swing, but his friend kept a hearty supply of liquor at his home, just like a good Catholic. David would have friends over to his “spacious apartment on Riverside Drive” almost every evening, and Fr. Pfau had a standing invitation. Enjoying the conversation and camaraderie, he was in the habit of having two Highballs at David’s place, never more.

Not finishing his Master’s degree at Fordham, Fr. Pfau moved back to Vincennes, and taught for three years. But he noticed that his drinking was beginning to increase. He says:

I drank regularly, but never really got drunk. I continued to maintain a certain amount of control; I never drank alone and never drank before noon. I was simply a social drinker, but I was always looking for someone to socialize with.1

A visit to St. Vincent’s Hospital

Liquor was still illegal, but he knew a bootlegger who was willing to drop off a supply of scotch when needed. Fr. Jerry, his brother, approached him about his drinking, telling him, “the Bishop’s got wind of it.” Fr. Pfau was directed to make a visit to St. Vincent’s hospital at the request of his bishop. It is at the hospital that he began to have suicidal thoughts:

Everyone is disgusted with me - the Bishop, the doctor, the other priests at Vincennes, Jerry, my other brothers, my friends - everyone. Nobody has any use for me any more. Why should they? I’m an absolute failure. Everything I touch turns to mud. I’ve never done anything to inspire anything but disgust. I’m no good to anyone - not even to myself.2

He paged a nurse and requested to see the hospital chaplain - Fr. Bauer. He went to confession and confessed suicidal thoughts, but the struggle was not over.

The Great Flood of ‘37 in Jeffersonville

He was stationed at St. Augustine’s in Jeffersonville, Indiana, in the 300 block on Locust Street.3 The year 1937 marked the eve of World War II, but it also meant the Great Flood. By mid-January of that year the weather had suddenly shifted, and “it became unseasonably warm.” He was stationed with another priest, Fr. Bryan. Beginning Jan 14th, it rained, and together with the heavy snows that year, the Ohio River began to swell; and by Thursday the 21st the water in Louisville had reached 48ft., breaking a record which had stood for half a century.

On the morning of the 22nd the two priests said morning Mass, and the parishioners assured them that all was safe because “we’re on the highest ground in town.” Fr. Pfau records that all heard a distant roar, and they all had a premonition that the dike had burst. Fr. Bryan rushed down to church to try and save the Blessed Sacrament, but Fr. Pfau pulled him back for fear that he would have drowned from the rushing waters. Fr. Pfau remarked, “Fr. Bryan was severely criticized for not having saved the Blessed Sacrament from the church, but there was nothing he could possibly have done. The waters were moving so fast that he was helpless.”4 He called Station WHAS in Louisville and told the operator that he was a Catholic priest and that seven people were stranded at St. Augustine’s parish house in Jeffersonville. After much prayer they were saved, and as Fr. Pfau sat in the safety boat, he said to himself, “I wanted to drink. There was no place to get one.”5

On to Snake Run, Indiana that is!

Fr. Pfau had been transferred to Snake Run, a place so remote that “there is not a smooth road within a radius of six miles within any direction.” The assistant pastor assured him that all was well even though the parish house had no electricity, no heating system, and no inside plumbing, with an outhouse near the back. Two Sundays later he said Mass at a church called St. Bernard’s. He told the parishioners that for twenty-one dollars he could get a toilet installed in the parish house, prompting one farmer to remark, “Twenty-one dollars for a toilet? What’s the matter with the toilet you got?”6 His Snake Run duties ended in the summer of 1939 when he received a letter informing him that his new assignment was to assist Fr. Ambrose at Holy Rosary Church in Indianapolis.

Off to Indy!

He reported to the bishop as soon as he arrived in Indianapolis. The bishop said, “I have reports that you have been visiting taverns.” Fr. Pfau answered, “I’ve never been in a tavern in my life,” which was probably the truth. While in Indy, he took another trip to a sanitarium in Chicago; and when asked by the doctor, “Do you drink much?" he answered more of the same, “Just once in a while.” The penitential time of Lent was approaching and he decided to give up alcohol. He lasted ten days.

He was working alongside Fr. Sullivan at Holy Rosary parish when Pearl Harbor happened on December 7th, 1941. Fr. Sullivan was in the National Guard and received deployment orders to go to the warfront. This prompted the bishop to send Fr. Pfau to St. Anne’s parish, in a nice part of town. But as Fr. Pfau put it, “The blow came in May of 1943” when the bishop ordered him to attend the Alexian Brothers Sanitarium in Chicago. The Brothers sent him to Winnebago State Hospital in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, for a few shock treatments. The A.A. shock would come later.

Time for an A.A. Meeting

Back at his parish duties at St. Anne’s, one day he got a phone call from a lady, “Fr., please come over, my dad - I’m afraid he dropped dead.” Fr. Pfau made his way to the house, just as the doctor arrived, but it appears the man had just passed out from too much booze. As Fr. was leaving the house he saw a book on the shelf, Alcoholics Anonymous, and asked to borrow it. They obliged. Fr. spent the next few weeks reading Alcoholics Anonymous, adding, “it was seared in my brain, word for word, comma for comma, question mark for question mark. I knew it from cover to cover, the stories, the philosophy, the questions, the answers- everything.”7 That night the priests were at table having dinner, and Fr. Pfau asked Msgr. Bosler about some Alcoholics Anonymous literature which had been left in the house. “Doherty Sheerin asked me if it was alright to leave it there,” the monsignor replied, “He’s a fine man- one of our most devoted parishioners. Comes from an outstanding family. I think he’s the president or something of A.A. here in Indianapolis.”8

That night Fr. Pfau called Doherty, and they agreed to meet. It was November 10th, 1943, Fr. Pfau’s thirty-ninth birthday. Doherty, who went by ‘Dohr,’ explained A.A. to Fr. Pfau, “We don’t teach anything. We don’t lecture anybody, or tell anybody whether he is or is not an alcoholic. All we do is suggest.”9 Dohr invited Fr. Pfau to come to his first A.A. meeting at Rauh Library, 8pm, Thursday night. There were seven people at that first meeting, and Dohr introduced Fr. Pfau by telling the guys, “I want to introduce a friend of mine, a new member, Fr. Pfau.”10 Dohr drove Fr. Pfau back to the priest’s house after the meeting, but Fr. Pfau denied being an alcoholic. Dohr’s logical reply had weight, “You wouldn’t be here with me, riding in my car on your way home from an A.A. meeting - you surely wouldn’t have contacted A.A. or anyone in it- unless you thought you had an alcoholic problem.”11 A good point!

Fr. Pfau fell into the intellectual trap that virtually comes with any Catholic alcoholic - why cannot I stay sober on the Church alone? Dohr summed it up to Fr. Pfau in this way:

Any good Catholic must have the Church. A.A. without the Church would be less effective for us than the Church without A.A. But, in order to stop drinking, people like you and me must have both. We need something to help us remove the natural obstacles to grace, something to keep us convinced we can’t drink - that we’re still alcoholics.12

Fr. Pfau would go on to stay sober, write books, travel extensively (750,000 miles / 10 years), giving alcoholic retreats, and contributing to the early history of A.A. He died Feruary 19th, 1967, with over twenty five years of sobriety.

Prodigal Shepherd. Fr. Ralph Pfau and Al Hirshberg. 1958.

ibid. p. 85

St. Augustine’s is a particular interest to the writer because, as a traditional Catholic, my own priest was baptized at this very same church, and his parents married there.

ibid. p.116.

ibid. p. 120.

ibid. p. 128.

ibid. p. 191.

ibid. p. 192.

ibid. p. 195.

ibid. p. 196.

ibid. p. 200.

ibid. p. 206.