A Personal Story about Talbot

“It was 2014, the day after St. Patrick’s Day, and I was walking with my buddies in Dublin, Ireland. It was about about noon and I was craving a pint of brew, so we stopped at a convenience store for my needed pint. The beer was a pop-top, and the Muslim store owner would not open it for me, but no worries, I popped it on a concrete wall.

Craving some alone time, I told my buddies that we would meet up in a couple of hours. We split ways. Here I was, alone, in a park, empty beer bottle in hand, looking for a garbage can. I prayed to St. Anthony, seeking to find a garbage can. I came upon a bronze statue of a man sitting alone on a park bench. This was odd. I instinctively knew, it was Matthew Talbot. “How poetic,” I thought to myself, “the patron saint of alcoholics, dying alone on a park bench, on his way to church.” I dropped to my knees, empty beer bottle in hand, and asked Matt Talbot to pray for me. I knew that it was time to get sober again, and I did, nearly two years later, on January 6th.”

His Life and Sobriety

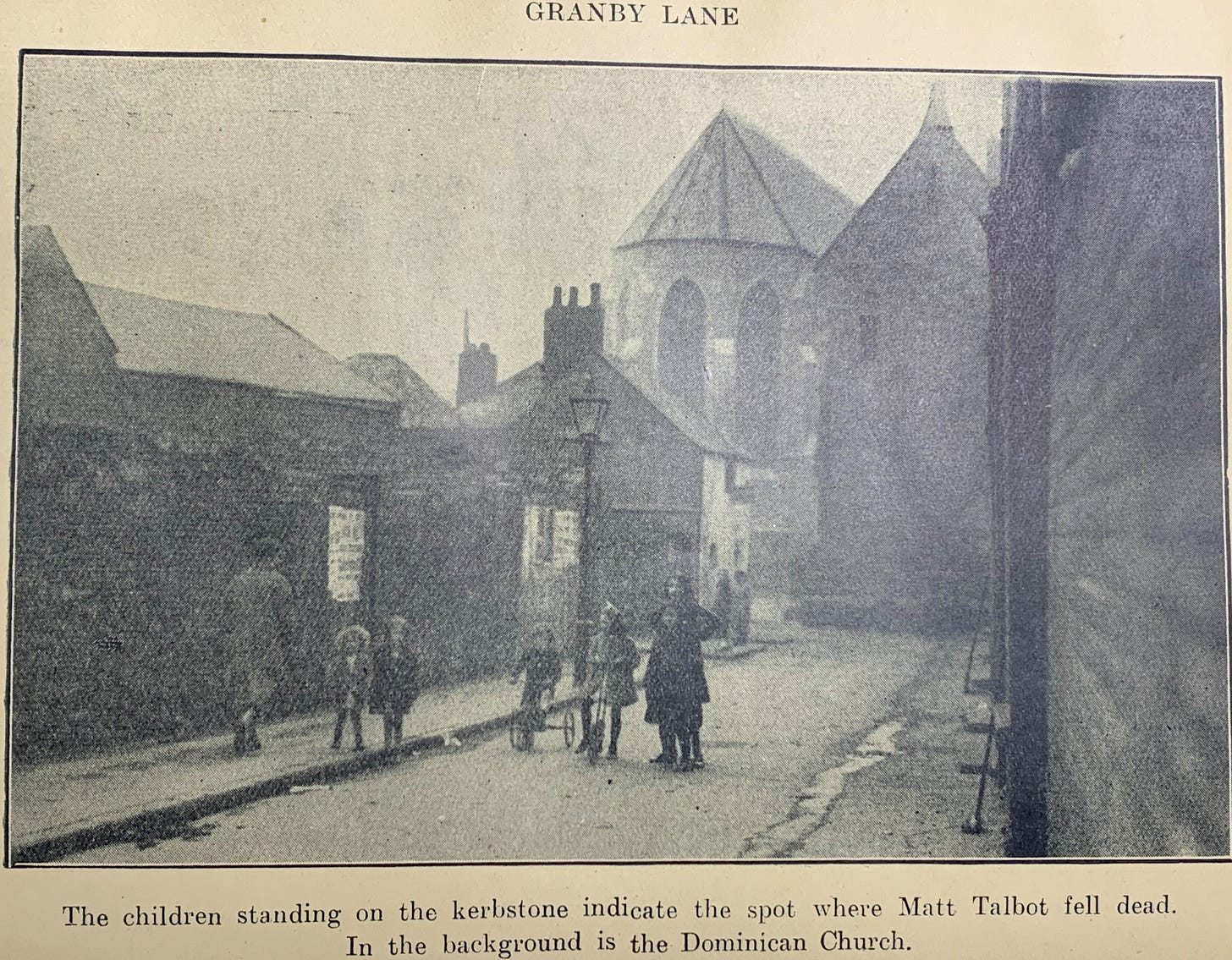

Talbot was a relative unknown, even in his own town of Dublin. The Irish Independent reported of his death, “An elderly man collapsed in Granby Lane yesterday, and on being taken to Jervis Street hospital, he was found dead. He was wearing a tweed suit, but there was nothing to identify who he was.”1

He was born on May 2nd, 1856, to Charles and Elizabeth Talbot, the proud parents of twelve children, eight boys and four girls. It appears by all accounts that the family liked drink; indeed, all of his brothers, save one, John, appears to have been alcoholic. His parents had their struggles in 19th century Ireland, having moved eleven times during their first eighteen years of marriage. Talbot’s first biographer, Joseph Glynn, says of them, “Both she and her husband were total abstainers; she, probably, from childhood, and he from manhood. The unfortunate habit of indulging in strong drink to which their sons were addicted was not, therefore, attributable to any laxity in this matter in the parental home.”2

He was a typical alcoholic; he would sometimes come home on Saturday night wearing no shoes, having sold shirt or shoes for a pint of beer. He once stole a blind man’s fiddle so that he and his friends might imbibe in a few drinks. He later regretted this thievery, and, in fact, located the blind man in a bar, trying to “make an amends,” but the blind man was too drunk to remember or care about the fiddle. Matt decided to have some Masses said for the blind man since he could not find and replace his fiddle.

He got sober in 1884, his twenty-eighth year, and life was not easy in early sobriety. He would carry no money in his pockets, lest he buy a drink. He would often change his walking routes around the city so as to avoid his favorite pubs. He redoubled his prayers, attending Mass every day; and three Masses on Sunday. His daily prayer routine was staggering: fifteen mysteries of the Rosary of Our Lady; the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin; the Dolor beads; the beads of the Immaculate Conception; the beads of the Holy Ghost; the beads of St. Michael; the beads of the Sacred Heart; the chaplet for the Souls in Purgatory, the litanies, etc.3 In addition to prayers his physical penances were extraordinary: Sleeping on a wooden board, wearing chains around his chest and leg, kneeling in church and home for long stretches, etc.

Matt’s sister was once struggling to cope with her alcoholic husband who had just become newly sober. Matt gave her a solid admonition, “Remember that it is very difficult for an alcoholic to get sober; be patient with him and remember, for the alcoholic to get sober is a greater miracle than for a man to be raised from the dead.” He joined The Pioneer Abstinence Association of the Sacred Heart, becoming member # 113. The movement was founded by Fr. James Cullen, S.J. for the purpose of combating “the widespread abuse of alcohol in Ireland.” The first temperance society in Ireland, the St. Paul Temperance Society, was started by a Franciscan, Fr. Theobald Matthews. Sister Katherine, MICM, gives us a history:

It was originally an anti-drink movement founded by a Quaker and was taken over by this priest who succeeded in overcoming his own addiction by making a pledge…The number of pledges soared to 7,000,000 souls who stopped drinking, but the movement did not last long. It started in 1838 and died out with the famine. Fr. Matthews died (Dec. 8) the year Matthew Talbot was born, 1856, and so did his movement.4

One of Fr. Matthews’ biographers, Dr. Rodgers, says, “Of the five millions of Irish people who had taken the pledge, only some hundred thousand had remained faithful.”

His Influence on A.A.

Readers familiar with the history of Alcoholics Anonymous (A.A.) will find this particular fact of interest: Matt Talbot, the patron of recovering alcoholics, was buried in Dublin, Ireland, on May 11th, 1925. May 10th, 1935, exactly ten years later, commemorates the founding of A.A. This is the sobriety date of Dr. Robert Smith, one of A.A.’s two co-founders. This date marks the birth of A.A. Founder’s Day is held every year during the weekend of May 10th, in Akron, Ohio.

Matt Talbot’s life had an influence on the early formation of Alcoholics Anonymous, albeit indirectly. Some literature which speaks of Talbot often mentions A.A., directly relating A.A.’s Twelve Steps to Matt’s life. One priest, Fr. Edward Dowling, S.J. (d. 1960), personally knew Bill Wilson (the other co-founder of A.A.), and said the following about the Program:

Alcoholics Anonymous is natural; it is natural at the point where nature comes closest to the supernatural, namely in humiliations and in consequent humility. There is something spiritual about an art museum or a symphony, and the Catholic Church approves of our use of them. There is something spiritual about A.A. too, and catholic participation in it almost invariably results in poor Catholics becoming better Catholics. 5

Matt Talbot’s View of Newspaper Reading

It would be unfair if we did not close this essay without giving Talbot’s view of newspapers. He had in his possession a lecture by Bishop John Hedley (d.1915), and the following passage was specifically marked. Today this quote concerning newspapers might certainly be applied to the internet, distracted creatures we are:

Even when the newspaper is free from objection, it is easy to lose a good deal of time over it. It may be necessary and convenient to know what is going on in the world. But there can be no need of our observing all the rumors, all the guesses and gossip, all the petty incidents, all the innumerable paragraphs in which the solid news appears half-drowned, like the houses and hedges when the floods are out. This is idle and is absolutely bad for the brain and character…As the reader takes in all this prepared and digested matter he is deluded with the notion that he is thinking and exercising his mind. He is doing nothing of the kind. He is putting on another man’s clothes, and fitting himself out with another man’s ideas. To do this habitually is to live the life of a child; one is amused and occupied, and one is enabled to talk second-hand talk; but that is all. Men were better men, if they thought at all, in the days when there was less to read…Immoderate newspaper reading leads, therefore, to much loss of time, and does no good, either to the mind or to the heart.6

Matthew Talbot, ora pro nobis!

Post Scriptum - This article was begun on Aug. 8th, the birthday of Dr. Robert Smith, as well as the feast day of St. John Vianney.

“Venerable Matt Talbot: Recovered Alcoholic.” Sister Katherine Maria, MICM. From the Housetops. vol. 55, no 1, serial # 107

Life of Matt Talbot (1856-1925). Glynn, Sir Joseph. 1930. 2nd Ed.

ibid.

“Venerable Matt Talbot: Recovered Alcoholic.” Sister Katherine Maria, MICM. From the Housetops. vol. 55. no 1, serial # 107

ibid.

Matt Talbot and His Times. Purcell, Mary. Franciscan Herald Press. 1976. p. 103.